BIM Requires New Thinking

This article was written by Geraldine Rayner for the Winter 2016 issue of Plumbing & Mechanical. View the original here.

Once upon a time, design consultants would generate design documents by drawing on trace and Mylar, the equivalent of driving a horse and buggy on the road. Then along came ‘Computer Aided Drafting’ (CAD) which was going to make our lives so much easier! The change from manual drafting to CAD was like replacing the horse and buggy with a car; same process, different tool. We are still, though, generating disconnected drawings and diagrams to represent what is to be built.

The productivity and statistics accumulated over the past few decades would indicate that this is not working very well. Productivity is down and change orders are up. Our clients, the owners and operators of the facilities we design, are understandably fed up.

So, how do we solve these problems? Most aspects of our modern lives, from television to music, email and even our phones, are now digital. We no longer use paper telephone di- rectories to look up numbers. We search digi- tally, select the number we want and the phone connects us. W hen we switch mobiles, we do not print out the entire contact list and then manually re-enter it into the new device. W hen it comes to construction documents, though, this is still generally considered acceptable. Our clients are expected to search through pa- per drawings and binders in order to validate data before manually re-entering it into end- source software for facilities.

We interact with computers and digital data in almost ever y aspect of our daily lives, yet the architectural engineering and construction industr y (AEC) is lagging behind. The term BIM is used widely with no clear definition attached to it. Some consider it simply a piece of software, while others think of it only in terms of 3D. The truth is that it is a process, with database software at its core that changes the dynamics of how we work . Now the data can be displayed in a way that supports the communication of design intent. It has intelligence and, when structured properly, it can be exported and consumed by other software solutions.

As objects understand their size and location relative to other objects, we have a choice regarding how they are viewed, whether it be conventional plan, section and elevation or 3D, with or without colour to aid in identification. Also, since views are queries of a dataset, if any thing is altered, then ever y view showing that object is automatically updated. Refer- ring back to the earlier analogy of a horse and buggy and a car, compared to manual drafting and CAD, adopting BIM is like taking a flight. The process involved is totally different. It goes beyond a simple change in the design of the vehicle. Planes are not designed to travel on roads.

Like flying, a BIM process requires discipline and adherence to rules if we wish to enjoy the benefits. It blurs the lines between different scopes, requiring cooperation and collaboration in order to share and use the work output of others.

Based on the testimonials of those who have redesigned their design process to meet the requirements of a BIM process, the rewards far outweigh the effort. Does it require a rethink in our fee structure and contracts? Yes. Should we be rewarded for bringing additional value, beyond what we are currently required to do? Certainly.

W hat happens if we don’t change? To quote from ‘Design at the Speed of Thoughtware’ by Paul Doherty (president/CEO of the digit group inc.), “…the old ways of doing things are just not sustainable. Aptitudes for change and growth are the single biggest challenges to the design profession. …W hen the dust from the transition to the New Economy settles, the architectural landscape will be strewn with car- cases of firms that were unable to adapt. Don’t let yours be among them.”

Mechanical and electrical (M&E) consultants and contractors are not excluded from this situation. The majority of issues on site are due to lack of coordination between disciplines. Firms that resolve them while digital, avoiding delays and cost creep, will become owners’ preferred partners and the downstream benefits of structured digital data will greatly offset the initial cost.

We live in a 3D world, so why would we not choose to work in a 3D design environment? Historically, mechanical and electrical drawings have been diagrams, with symbols representing design intent. BIM requires a rethink with regard to planning and communication with other disciplines. Since it relies on realism for clash coordination, for example, ducts and pipes need to be modeled accurately, complete with bends and slopes.

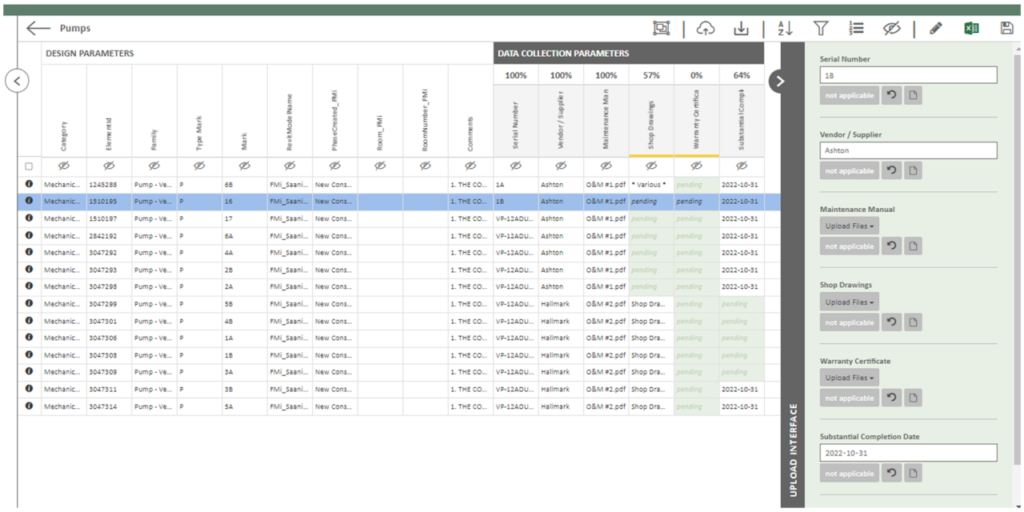

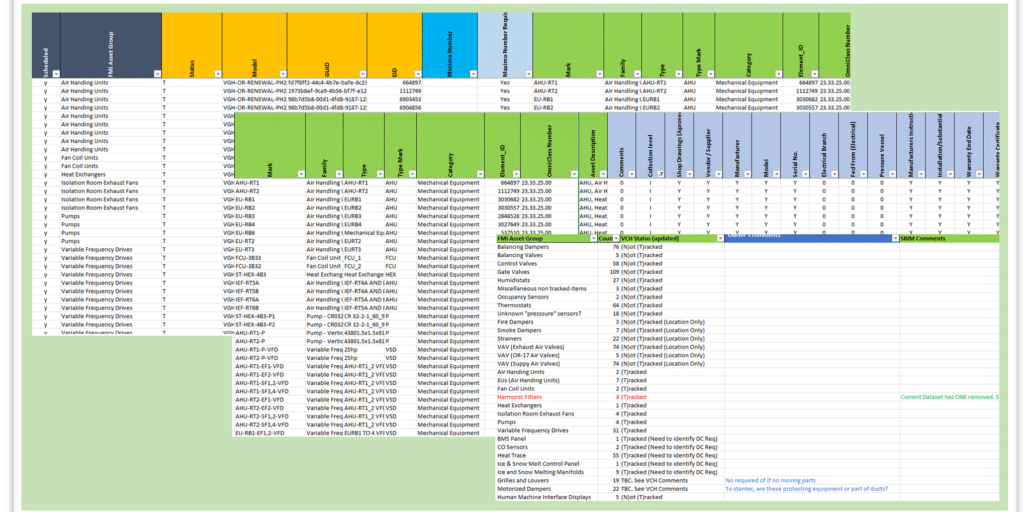

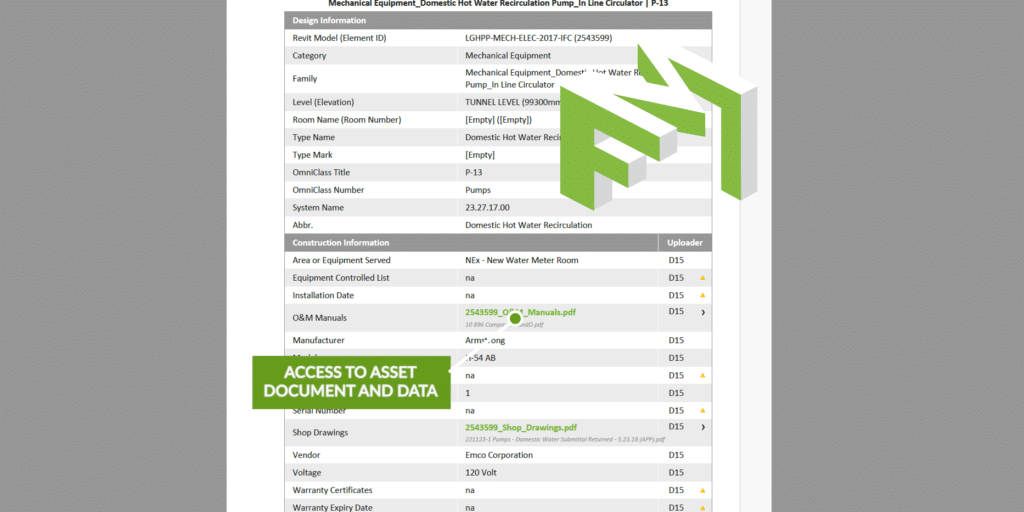

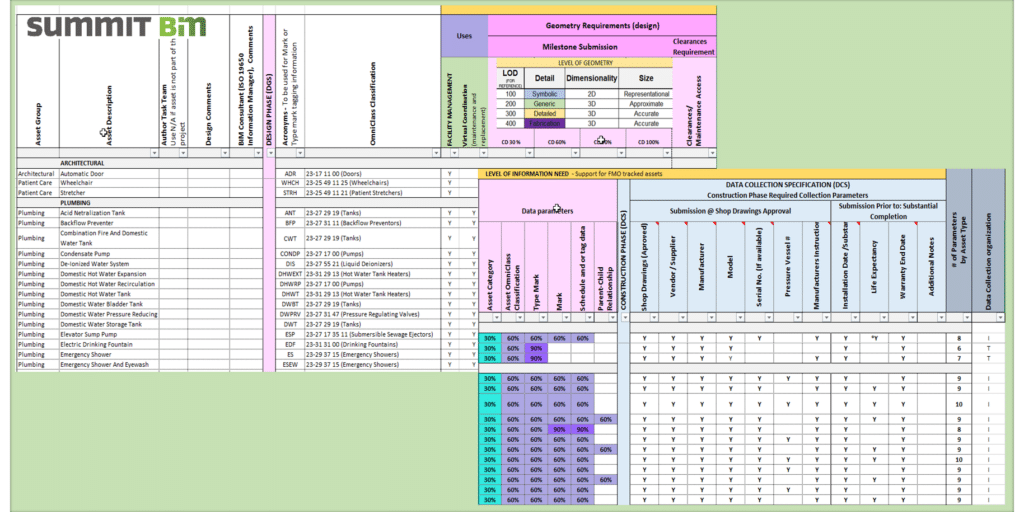

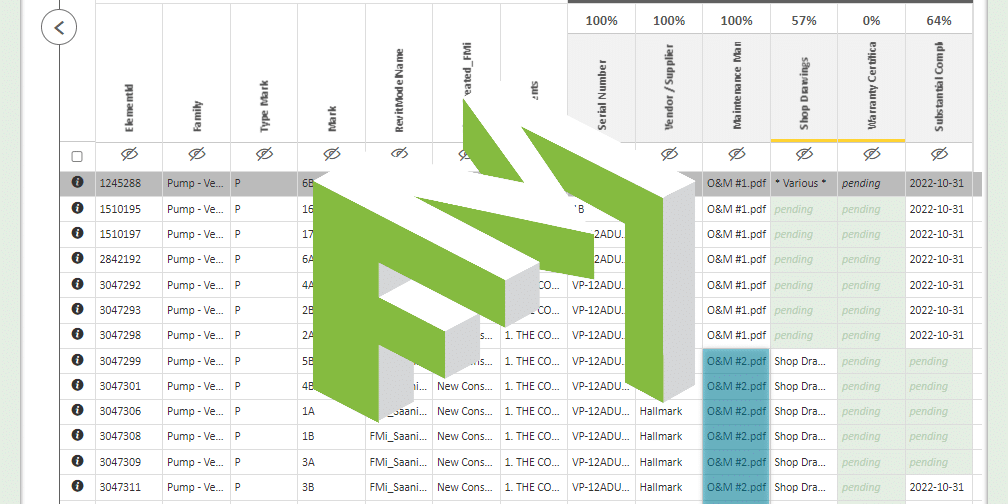

Owners are now being offered final deliverables consisting of an interactive dataset with a graphic and report view, where all information is linked to the related objects and the graphic views show what really matters to facilities. It is collected digitally during construction and provided at handover, not months later. This structured data set can then be mapped to end source software. No more manual data entry.

Since design fees typically account for only 2 per cent of lifecycle costs, given a choice between a low design fee based on a paper-based process subject to the inherent problems noted above and a more expensive digital process that avoids time and cost overruns and provides a digital handover, it is reasonable to expect that owners will increasingly choose the latter option. Firms, including M&E, that offer this option will survive and thrive in these changing times.

Related Posts

Data Collection through Construction

Coming to Canada: A BIM Consultant’s Journey

BIM and the Art of an Asset Registry

Digital Handover – a less stressful solution

DGS/DCS Evolution – A Retrospective

Data Visualization and Collection for FM Handover

Data and Document Collection for FM Handover